20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-001

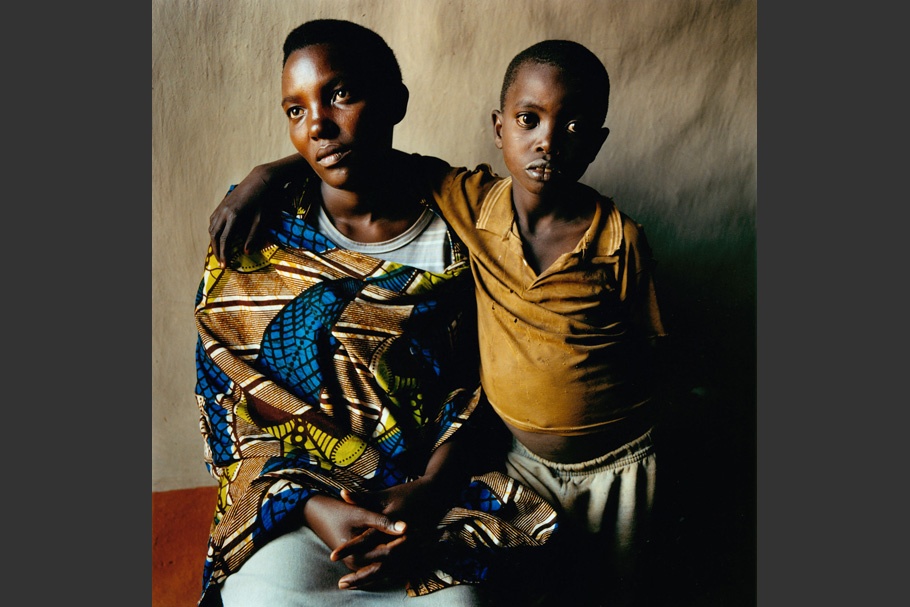

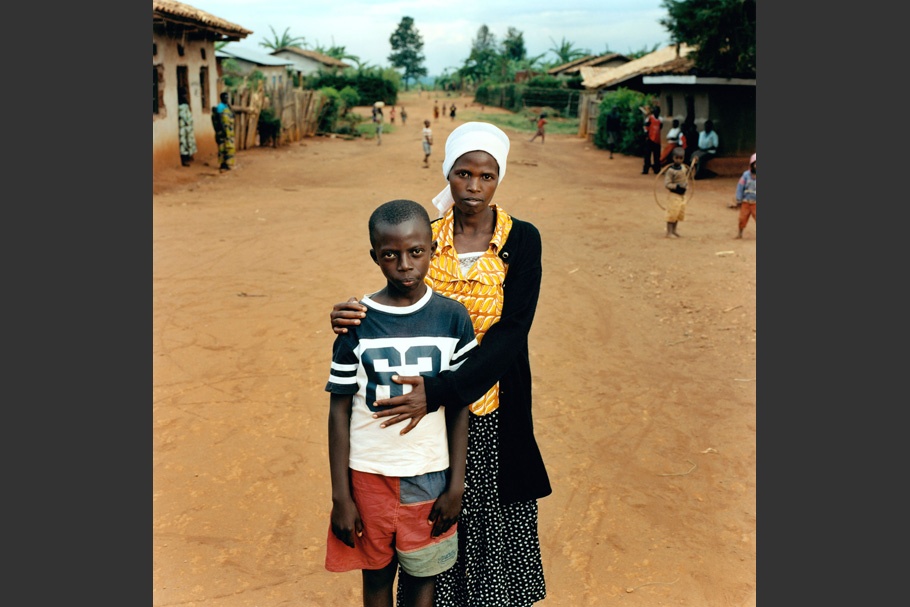

"The militiaman took me to his house, and raped me for the two weeks I was there. He later took me with him to exile in Tanzania, and continued raping me the whole time. I got pregnant from these continuous rapes. When he heard I was pregnant, he declared I was his wife. I had no choice but to stay as 'wife' to him." —Valerie, 27, with her son Robert, 11

Mwurire, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-002

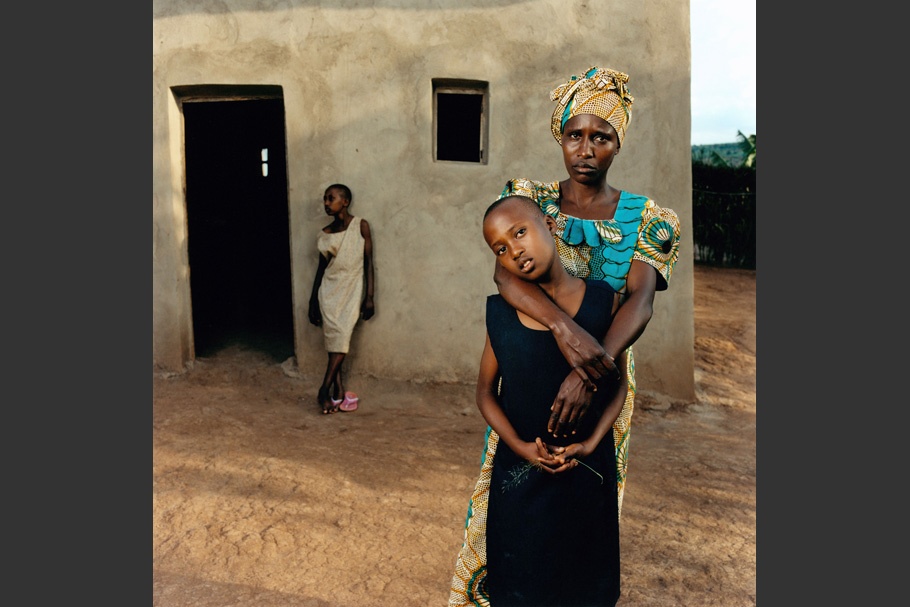

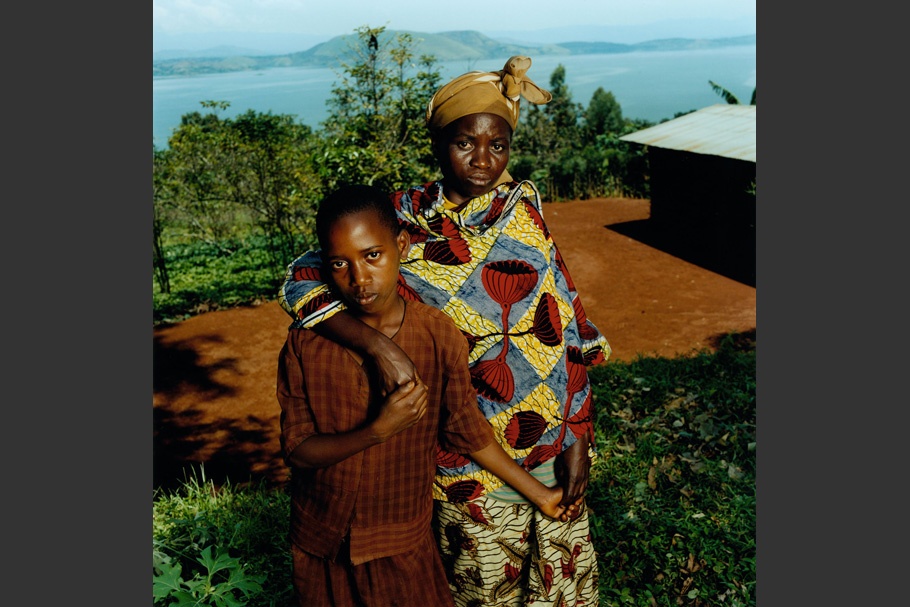

"I fail in my duty as a mother because of poverty. I don’t see any future for me. I sometimes look at my situation and compare myself with those people that have their families around them, and I regret I did not die in the genocide. Up to now, I wonder why the genocide did not take my life." —Isabelle, 27, with her son Jean-Paul, 11

Kayonza, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-003

"I was in the church with my three children when the militiamen started cutting people into pieces, but premonition was telling me to pick one child and run away. Maybe I would survive. But I looked at all three and they all looked so nice to me that I could not pick one, until my heart told me to take the first born, so I took him and ran toward the church door." —Olivia, 43, with her son Marco, 11

Shangi, Cyangugu, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-004

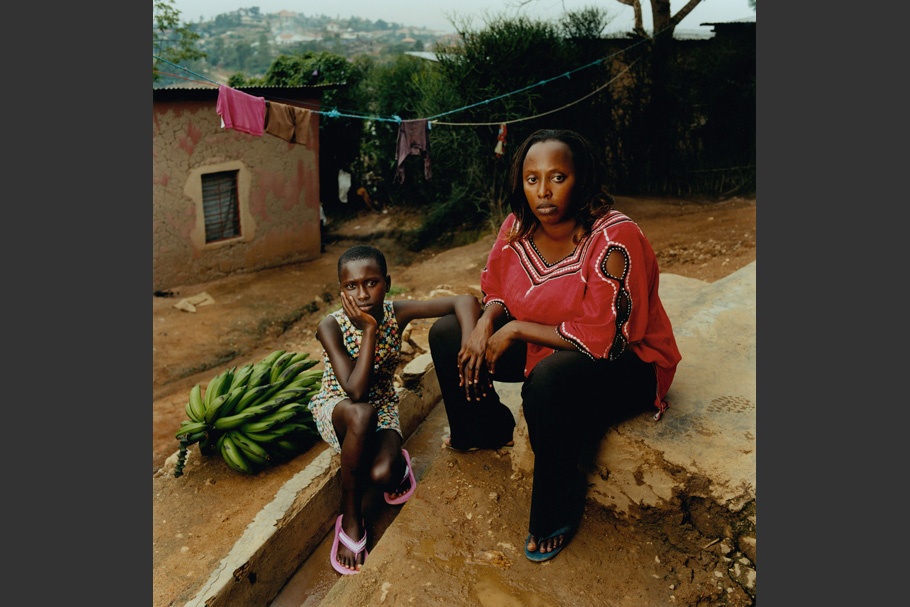

"That night when the head of the militias came to rape me, he told me I was not the first that he had raped. He was ruthless, he pierced my leg with a spear, forcing my legs apart, and he raped me for four hours. I stayed in that place being raped every night for six days...Why I love the first daughter more is because I gave birth to her as a result of love. The father was my husband. The second girl is unwanted, the result of rape." —Valentine, 37, with her daughter Amelie, 11

Gishari, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-005

"Maybe, with time I will love this daughter of mine, but for now 'no.' Sometimes I regret not having an abortion and sometimes, because she is the only daughter that I am going to have in my life, I don't regret. So it is mixed feelings. Sometimes I blame God. For a long time, I've really hated God. I've asked myself, Why did people die? Why did my family die? Why this extreme violence? Why am I HIV positive? All these questions, I said there is no God." —Philomena, 26, with her daughter Juliette, 11

Gasabo, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-006

"When I realized I was pregnant from the rape, I started wishing to die. I even thought of committing suicide. Then I feared committing suicide and felt that I should give birth to that kid and kill it. But when I gave birth the child was so beautiful that I loved him immediately. I couldn't kill him, I will love him." —Marie, 34, with her son Isaac, 11

Rusizi, Cyangugu, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-007

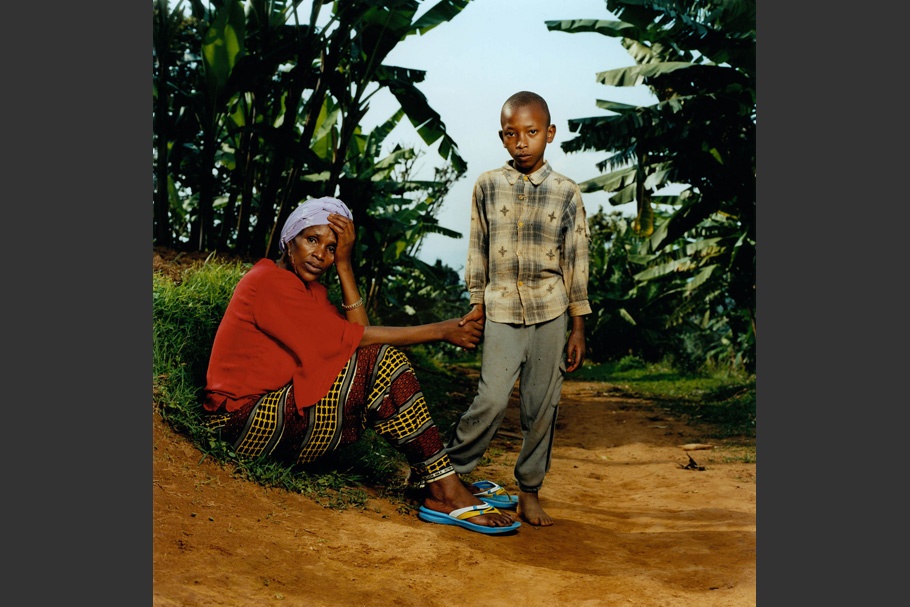

"Tell the world about the aftermath of genocide, that the effects of genocide are still heavy on us. We need support, we need prayers for us to live as human beings. The life I live now is directly related to what I went through in the genocide so the world should come and help us deal with it, should be near us and close to us in dealing with the aftermath of genocide." —Bernadette, 43, with her son Faustin, 11

Rusizi, Cyangugu, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-008

"The only problem I have is providing for my son. When I think about his life, he is like a tree without branches. I am alone. I don't have any surviving relative apart from my old mother. He is my life. He is the only life I have. I love him. If I don’t have him, I don’t know what I would be." —Stella, 30, with her son Claude, 11

Sahera, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-009

"I cannot really tell you how many men came to rape me. I cannot count them. All I saw was that four months later I was pregnant. I felt so bad. I tried committing suicide twice. I now live with HIV/AIDS as a legacy of the genocide. They raped us, it was really brutal. Six, seven men, all of them, one after the other in turn they go, once they are all done they all come back the next day—the same again. I don’t have words. I don’t want to think about it again. We begged them to kill us. They refused. They kept taking us to the roadblocks and making us sit there as they did their killing jobs and after killing, they came to rape us." —Sylvina, 34, with her daughter Marianne, 11

Kimironko, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-010

"The militiamen came and collected us from that room and took us behind the church to a banana plantation and then they started raping me. One of them took me as a sex slave for three days. We went in a church because we thought that the church was safe. Everyone in my family was killed in that church except me." —Justine, 35, with her daughter Alice, 11

Gahini, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-011

At night he came and raped me. His wife was there but he never bothered about his wife. After raping me that night he put the spear near me, and said I shouldn’t move. If I move, I will be killed. From that day on, he said, I was his second official wife. So in that man’s house I stayed as a wife. He went to kill, he came back. He went to kill, he came back. I never moved out of this village. I was in that house for about four months. I don't have any feelings whatsoever for this man. I never loved him. He was married, he had four children. I was still a virgin, I had never had sex before." —Chantal, 32, with her daughter Lucie, 11

Shangi, Cyangugu, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-012

“What happened in this country in 1994? We have families that were broken and torn up. We have people who were dehumanized and treated like animals. Even animals could have value sometimes. I want the world to ensure that everybody’s human rights are protected. Every effort should be made to ensure that rape and acts of sexual violence never happen to anyone, because they affect not only the victims but the children that come after.” —Odette, 28, with her son Martin, 11

Rawamagana, Rwanda.

20080313-torgovnik-mw14-collection-013

"I never loved this child. I was torn between two worlds. I forced myself to like him, but he is unlikable. The boy is too stubborn. He behaves like a street child. I don't show him that I don't like him. He is a terrible bad boy. It's not that he knows that I don't love him, it's that blood in him." —Josette, 26, with her son Thomas, 11

Gisazi, Rwanda.

Jonathan Torgovnik was born in Israel in 1969 and graduated with a BFA from New York's School of Visual Arts. His photographs have appeared in numerous international publications, including Newsweek, Aperture, GEO, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern, Smithsonian, and Paris Match. Torgovnik has had numerous solo and group exhibitions in the United States and Europe, and his photographs are in the permanent collections of museums such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

Torgovnik is the first prize recipient of the 2007 UK National Portrait Gallery's Portrait Prize and the recipient of the 2007 Getty Images Grant for Editorial Photography. The Open Society Foundations recently awarded him a Documentary Photography Project distribution grant. He has received awards from Picture of the Year International, American Photography, Graphis, Communication Arts, and Photo District News. Torgovnik's book Bollywood Dreams, an exploration of the motion picture industry and its culture in India, was published in 2003 by Phaidon Press.

Torgovnik, a contract photographer for Newsweek since 2005, is on the faculty of the International Center of Photography School in New York.

Jonathan Torgovnik

In February of 2006, I traveled to East Africa to report on a story for Newsweek to mark the 25th year since the start of the AIDS epidemic. While in Rwanda, I heard the testimony of Odette, a survivor who was raped during the genocide, contracted HIV, and had a child as a result of the rape.

Later that year, I decided to return to Rwanda on my own accord and work on a personal project about women who were raped during the genocide and had a child as a result. I returned several times over the next two years, uncovering more details of the heinous crimes committed against these women. The mothers of these children, many of whom contracted HIV, have largely been shunned by their communities and their few surviving relatives due to the stigma of rape and “having a child of a militiaman.”

Thousands of Rwandan women were subjected to sexual violence perpetrated by members of Hutu militia groups. Some Tutsi women were attacked by individual militiamen, others were subjected to gang rape. Some were forced to witness the torture and killing of their entire families. Many were told, “You alone are being allowed to live, so that you may die of sadness.”

One victim, Sylvina, age 34, described her experience: “I cannot really tell you how many men came to rape me. All I saw was that four months later, I was pregnant. I tried committing suicide twice. I live with HIV/AIDS as a legacy of the genocide.”

More than a dozen years later, the legacy of genocide haunts these women, as they still struggle to restart their lives. They face numerous challenges: the stigma of rape, discrimination against them because they are HIV positive, and the difficulty of living in a community that has not yet dealt with the trauma and atrocities experienced during the genocide.

Some of these women have been unable to fully accept their child because they associate their son or daughter with the brutality perpetrated upon them. Others have accepted their child, but, in some cases, the mother’s decision to keep the child has caused her own family to ostracize her. In Rwanda, where extended families form the backbone of community life, such alienation can be devastating. The mothers feel they have lost their dignity; they are alone, cut off from emotional and financial support, and utterly powerless. For many survivors of the genocide, their own lives have become a form of torture.

These women, the only adults in their household, face the overwhelming task of rebuilding their lives, and providing food, shelter, and school fees for their children. “Even now, getting books, a pen, a uniform for him, it’s providence,” Bernadette said about the difficulty of caring for her son under these circumstances. “Sometimes he sits here for a whole term because I have failed to get pens and books. If there is anything that tortures me, it is the tomorrow of my son.”

The international community has already failed Rwanda. When reports circulated about the genocide and brutality, political leaders turned a blind eye. Rwanda may have survived the genocide, but many of its citizens are barely hanging on to their fragile existences. It is vital that these women’s stories are heard and that the survivors of the genocide are not simply forgotten as part of yesterday’s news.

I have changed the names of the mothers and the children, and given their ages at the time they were photographed.

—Jonathan Torgovnik, February 2008