20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-001

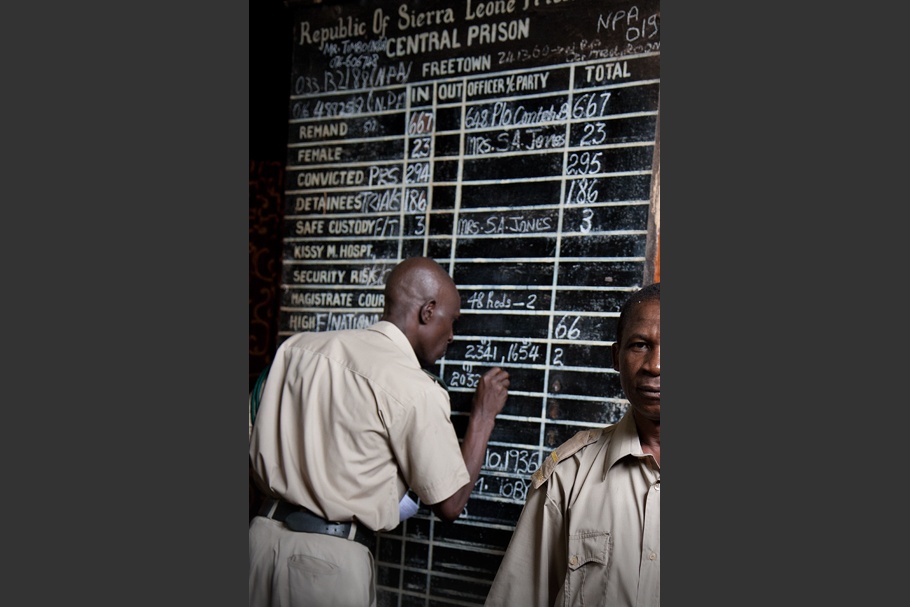

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Peter is one of the officers who escorts prisoners to court. Every morning dozens of the 1,300 men and boys held at the Pademba Road Prison are taken to court. Many of them go multiple times before receiving a sentence. One of the boys claims that he went to court more than 50 times. Prisoners can be remanded for years before they are sentenced.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-002

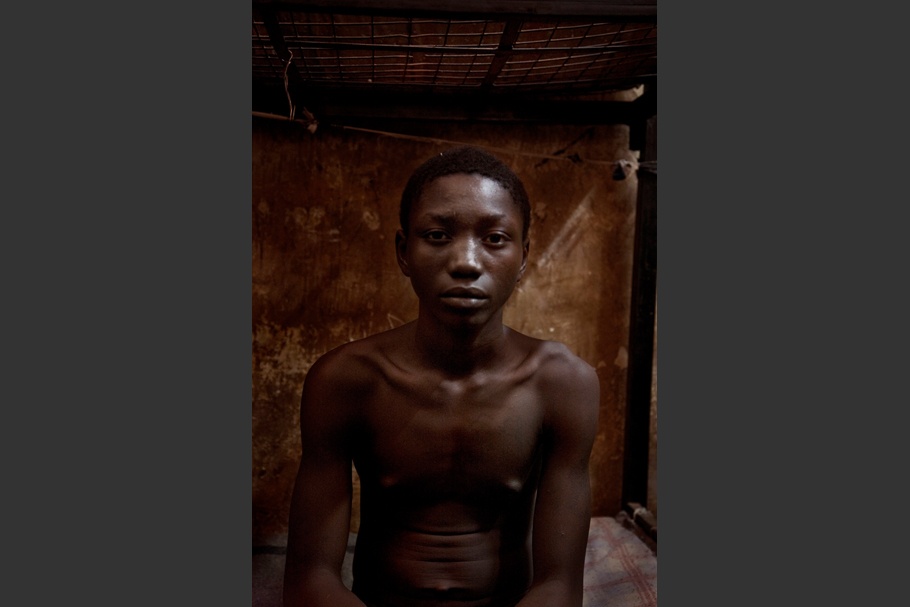

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, October 2010.

Fourteen-year-old Abdul Sesay appears at Court No. 2. On July 26, 2010, he was jailed in Pademba Road Prison. He was accused of having a portable radio that another man claimed belonged to him. The man hit Abdul very hard, resulting in injuries that have given Abdul breathing problems. Abdul was taken to the police station and held for eight days. The police have determined that Abdul is an adult. He was released on October 29, 2010, only after Moleres and John Carlin, a freelance journalist, made a bail payment of 320,000 leones (60 euros). Since November 2012, Abdul has been in school after participating in the Free Minor Africa rehabilitation program at the Saint Michael Center.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-003

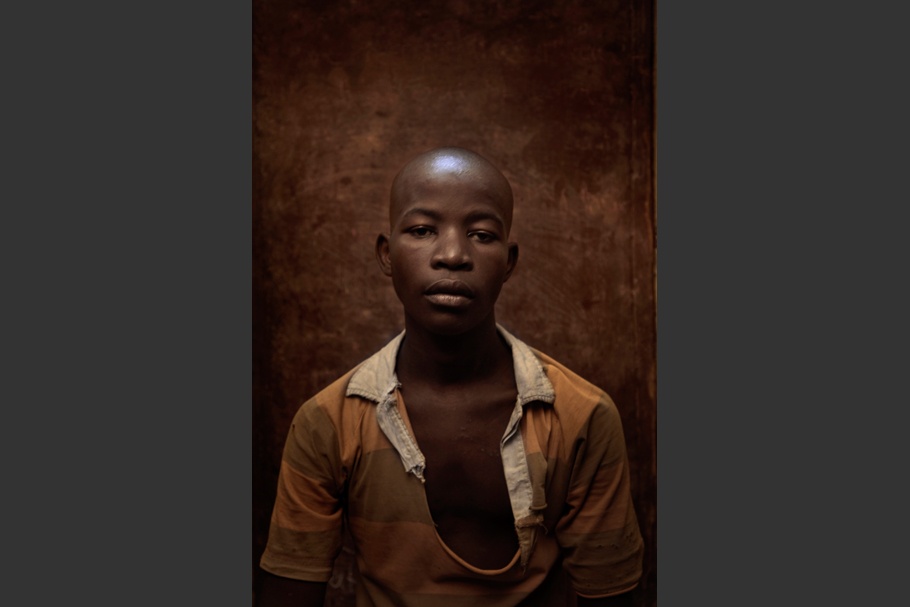

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Every morning dozens of men and boys from the Pademba Road Prison are taken to court. This does not mean that they will be judged; it may be years until their trials end. Some youth, like Abdul Karim Essay, may spend several years in Pademba Road Prison before receiving a sentence.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-004

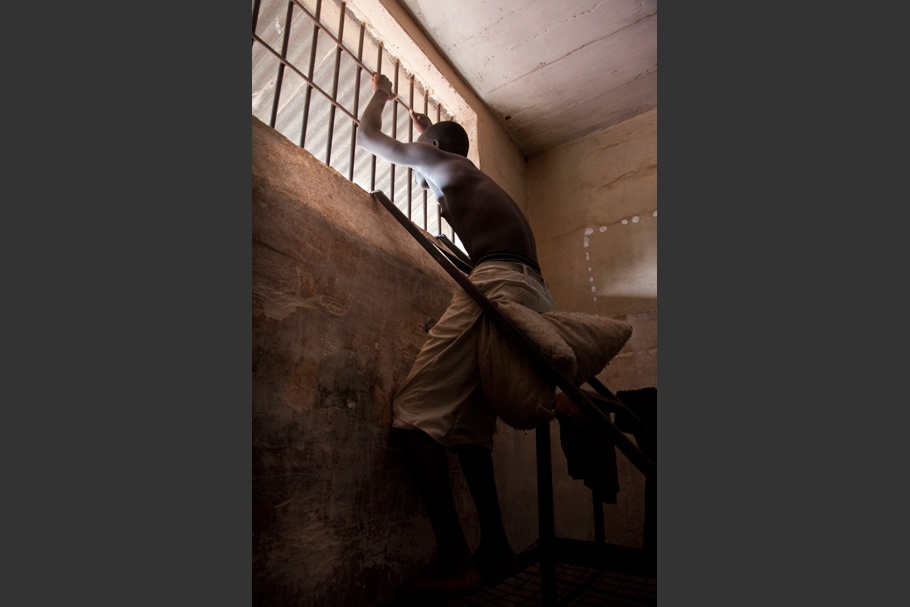

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Three hundred men and boys are held in block No. 4 at the Pademba Road Prison. A select few, such as foreign drug traffickers, have the money for individual cells. The majority of cells are overcrowded and many of the men and boys sleep on the floor.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-005

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Hilmami Musu Bangura, a 17-year-old orphan, was accused by his uncle of stealing his motorcycle. Hilmami received a four-year sentence. He has developed severe scabies and lives with seven others in a cell that has one dirty mattress on the floor.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-006

Makeni Prison. Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Thirty-four men and boys sleep in cell No. 3 at Makeni Prison, most of them on the floor. A prison privilege that allows them to occupy their time is the use of the facility’s two sewing machines.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-007

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Ibrahim Sesay is interrogated by prisoners about the disappearance of a pair of slippers from a cell. Ibrahim was arrested on August 24, 2009, after being accused of stealing a mobile phone at his school. He was held at the police station for eight days without food. Ibrahim says he is 14 years old, but the police recorded him as 19 years old, and he received the adult sentence of 18 months in prison.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-009

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

An officer sleeps in the prison registration room. The records for the prison’s approximately 1,300 prisoners are not well organized and are difficult to access. Many of the incarcerated men and boys have similar first and last names and prison officers are often careless and negligent when creating or using the documents. The average prison guard earns $60 a month and few candidates with strong administrative skills are attracted to the job. The haphazard record-keeping and administration result in many incarcerated men and boys waiting months or years before they go to trial.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-010

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Men and boys incarcerated at Pademba Road Prison crush potato and cassava leaves. This mixture, plus a bowl of rice, makes up the standard prison lunch. Breakfast consists of a cup of tea and a piece of bread. This limited diet contributes to vitamin deficiencies among the men and boys, leaving them weak and vulnerable to illness. Those with money can buy meat or fish, but this is a very rare luxury for most of the prison population.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-011

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Food is scarce in the prison. The only solid meal of the day consists of cassava leaves and rice. Water distribution is inconsistent and incarcerated men and boys sometimes do not receive the daily allocation of one-third of a liter of water. Younger, smaller members of the prison’s population suffer the most. Those with money can buy additional food and water, but most men and boys held at Pademba Road Prison are too poor or do not receive visits from people who could give them money or food.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-012

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Pademba Road Prison is Sierra Leone’s maximum-security prison. The prison’s guards are unarmed and it holds more than 30 children among a population of 1,300 inmates.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-013

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

A bucket at one end of the courtyard is the toilet for 240 men and boys held in the section for detainees whose cases have been remanded. Those who are convicted either pay for access to latrines or use an open area at the end of the yard.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-014

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Sarh Monserey (center) entered Pademba Road Prison in 2007. He was 13 years old and charged with murder. Sarh had gone down to the river with his best friend who subsequently drowned. The child’s family accused Sarh of murder, and he has spent the last four years in prison awaiting trial. Now 20 years old, Sarh will be released on July 4, 2013. Free Minor Africa and the Saint Michael Center will help Sarh find work and make the transition back to society.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-015

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, February 2010.

Sixty men and boys living in a 30-square-meter cell. They spend 16 hours a day in the cell, share a single bucket for a toilet, and have various diseases and infections, including scabies. Sometimes, they have to wait up to eight months for a single bar of soap that they will share among themselves.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-016

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Men taking a bath in the central courtyard of Pademba Road Prison.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-017

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Checkers is very popular among the men and boys in Pademba Road Prison. Sometimes they use fake money to gamble on the games, which usually results in serious arguments and fights.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-018

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2010.

Fourteen-year-old orphan Mohamed Conteh was arrested on December 2, 2009, for possession of cannabis and spent four days in the police station without food. The police offered to release him if he paid them a bribe of 30,000 leones (7 euros). Mohamed went to trial without any legal assistance or help from family members and received an 18-month sentence. Upon his release, Mohamed joined the Free Minor Africa rehabilitation program and began taking classes to get a driver’s license.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-019

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2010.

Mohamed Musa does not know his age or date of birth. He is a war orphan who was living with his uncle. His uncle accused him of stealing 10 gallons of palm oil and had him arrested. Mohamed was sentenced to two years in prison. Because he had no money, Mohamed was never able to buy soap and water to properly bathe himself while in prison.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-020

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2010.

On the day he entered prison, 16-year-old Abu Sese wrote “July 16, 2009” on the wall of his cell. Before he began serving his two-year sentence, Abu had gone to school up to the sixth grade and was working on a minibus. Family problems pushed him onto the streets. Eventually, he and another boy were caught stealing a purse. Abu’s family did not know that he was in jail. He had heard terrible things about the prison and was afraid he would be killed when he arrived. Once released in 2011, Abu was contacted by Free Minor Africa and invited to participate in a rehabilitation program. In January 2013, however, Abu was detained again and sent to Pademba Road Prison. He was eventually released and now lives on the streets with a gang near Victoria Park.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-021

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Maju Daramy was arrested in 2008 when he was 16 years old. He was accused of stealing a phone and sentenced to three years in prison. During his trial there were no formal complaints filed or witnesses used to verify the charges against him. Maju was eventually released from prison but his parents do not know where he is.

20130401-moreles-mw20-collection-022

Pademba Road Prison. Freetown, Sierra Leone, August 2010.

Young men at Pademba Road Prison bathing with rainwater. A benefit of the rainy season is that it allows prisoners to bathe easily and for free. Most prisons in Sierra Leone do not have running water. Sometimes drinking water is only available if inmates can pay for it. Buckets of water for bathing cost 1,000 leones (0.17 euros), a price many cannot afford.

Fernando Moleres was born in Bilbao, Spain, in 1963. He is a self-taught photographer who discovered photography while traveling and doing volunteer work as an activist, laborer, and medical nurse in Nicaragua.

Moleres has produced multiple reports on pressing social issues, such as refugees in Kurdistan and sub-Saharan Africa, and juveniles in African prisons. His books include Children at Work, published in 2000, which focuses on the systematic exploitation of child labor in more than 30 countries. Another publication, Men of God, explores monastic life.

Moleres received the World Press Photo Award in 1997 (series, daily life) and 2002 (series, art). In 2011, he won the World Press Photo Award daily life series again with Juveniles in Prison. In 1999 and 2011, Moleres won second prize and was a finalist, respectively, for the W. Eugene Smith Grant for Humanistic Photography. He won the World Press/Human Rights Watch Tim Hetherington Grant in 2012 for documenting prison conditions in Sierra Leone. His photographs have appeared in numerous publications including Courrier International, El Pais, Figaro, The Independent, Le Monde, Stern, and Time. Moleres’s work was exhibited at Visa pour L’Image International Festival of Photojournalism in 2000 and 2011. He is represented by laif, LUZ photo, and Panos Pictures.

Fernando Moleres

Papillon, Henri Charriere’s memoir describing prison life in colonial French Guiana, was one of the first books I chose to read on my own. I was riveted by its description of injustice but above all, how it spoke of people’s yearning for freedom.

My interest in injustice has also been fueled by direct personal experience. In the 1980s, I protested in Spain to support Basque independence. I traveled to Nicaragua in 1987 to help with the coffee harvest and serve as a nurse. There, I discovered photography as a valuable tool for creating dialogue about the injustices and struggles I encountered.

Lizzie Sadin’s 2007 photographic exhibition at the Visa pour l’Image festival in Perpignan, France, on incarcerated minors in Madagascar turned my attention to the horrible situation faced by juveniles detained in African prisons. Reports I read had few images to convey the grim conditions they described. I became determined to produce photography clearly depicting the conditions faced by minors in the Pademba Road Prison in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

When I arrived, the prison held 1,300 prisoners living in terrible conditions. Many of them spend years awaiting trial. There is no legal assistance to help them pursue their release. Hygiene is non-existent and food and water are scarce. Prison life is a struggle for survival, with adult prisoners often torturing and beating juvenile inmates.

My Sierra Leone prison photography has been published in the European press, but I feel that the story has not exposed a broad audience to this tragedy. I continue to think about people like 14-year-old Mohamed Conteh, a street orphan accused of possessing a small quantity of marijuana. The police denied Mohamed food for four days while he was in custody and demanded 30,000 leones (7.5 euros), which he did not have. After several months in prison awaiting trial, he was convicted and sentenced to either three years in jail or a fine of 100,000 leones (25 euros).

I have tried to build upon the awareness my images can generate by creating the Free Minor Africa initiative in 2012. The initiative offers legal aid, bail payments, and rehabilitation to those incarcerated for minor offenses. It also collaborates with the Saint Michael Center to provide shelter and education for juveniles who have served their sentences but have no family and few resources to help them reintegrate into society.

—Fernando Moleres, April 2013