tent-life-beauty-salon-mw19-collection

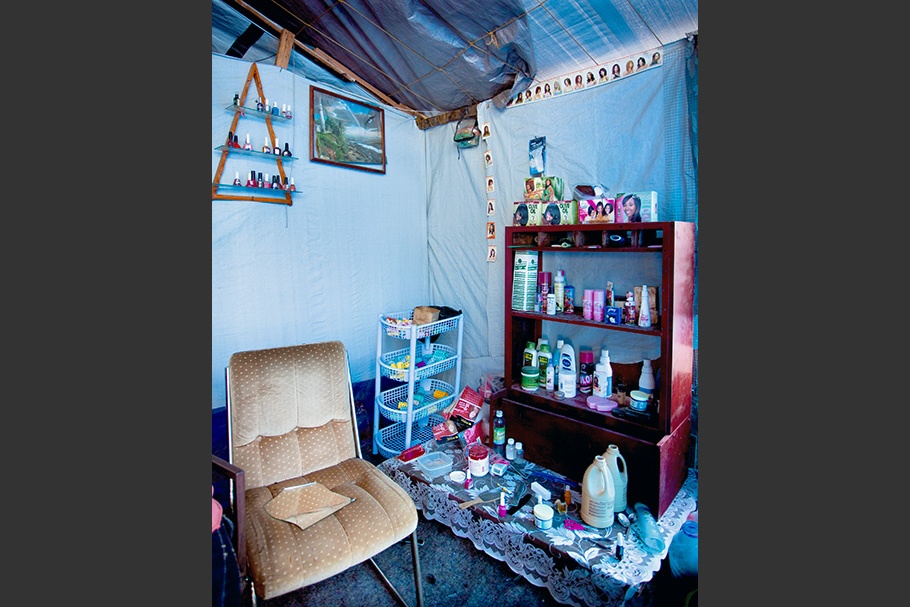

Julie Studio Beauté. Many beauty salons were formed within the tent communities after the earthquake. Spaces like these brought a sense of normalcy to life after the earthquake. Pétionville camp, Pétionville, Port-au-Prince, September 2010.

tent-life-vanessa-with-baby-mw19-collection

Vanessa’s baby was born eight days after the earthquake that killed her husband. She lives with her brother Wilson in a tent. Relief camp next to the airport, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-two-sisters-mw19-collection

Two sisters pose for their portrait in a makeshift photo studio. Bobby Duval Soccer Field relief camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-teenage-girl-mw19-collection

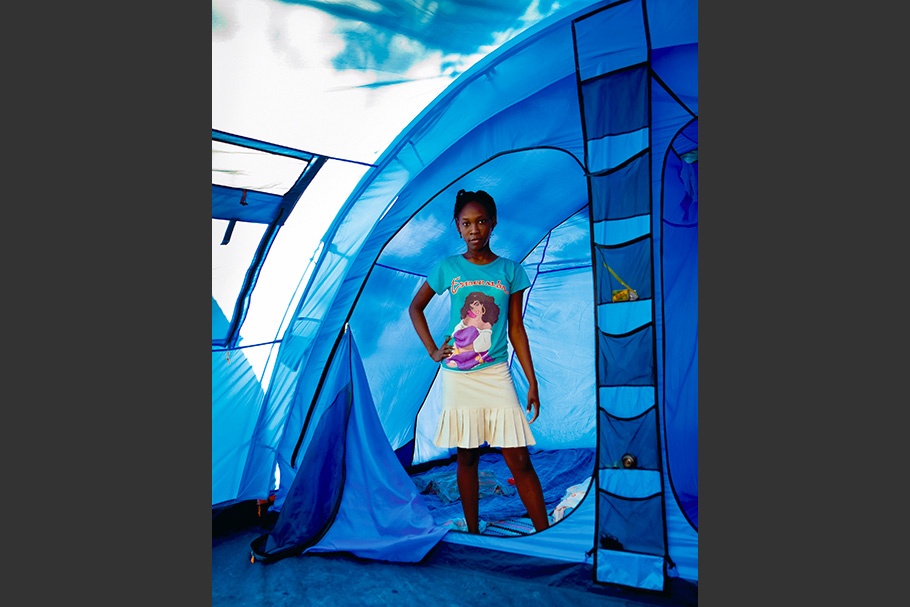

A teenage girl stands inside her family’s tent. Delmas 31 camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-orange-tent-mw19-collection

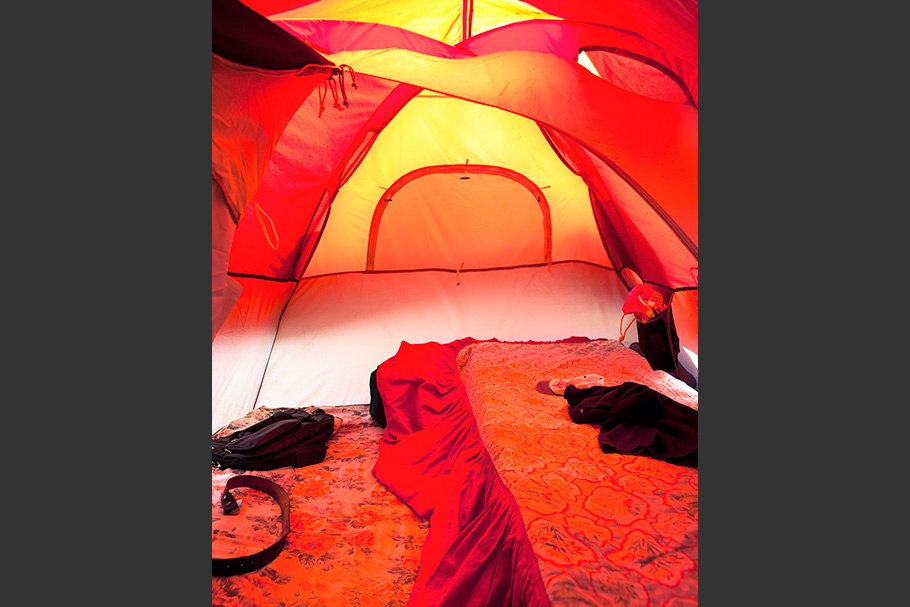

Four people share this camping tent at night. Delmas 31 camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-bright-yellow-mw19-collection

A plastic tarp casts a bright yellow light over this temporary home. The residents hang their clothes and possessions on the walls to keep them dry when it rains. Delmas 32 camp, Port-au-Prince, September 2010.

tent-life-blue-tarp-mw19-collection

A blue tarp over a white tent casts a deep blue light upon some cooking oil, a water bucket, and an axe—the few possessions that one family managed to recover after the earthquake. Relief camp next to the airport, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-girls-lying-down-mw19-collection

Two teenage girls in their sleeping space in a tent that they share with 12 people. Bobby Duval’s Soccer Field relief camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-woman-with-possessions-mw19-collection

A woman in her tarp-covered home next to the only possessions she has left. At night she rolls out her carpet to sleep. Delmas 31 camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-concrete-blocks-mw19-collection

A woman sits on her concrete-block bed with sheets set up for privacy and shelter. Delmas 31 camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-man-kneeling-mw19-collection

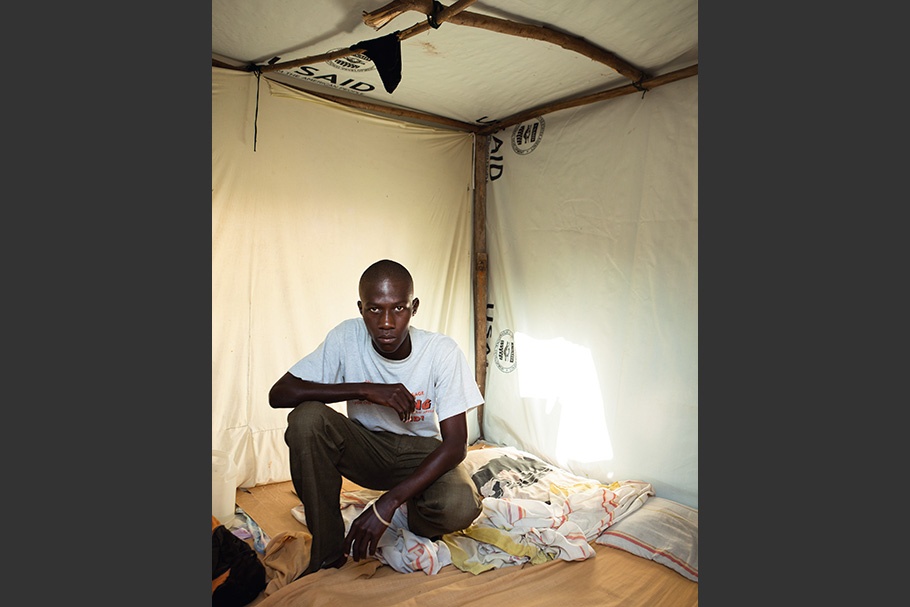

A man inside a relief tent held together with tarps and tree branches. Delmas 31 camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

tent-life-sitting-on-bed-mw19-collection

A woman sits within a shelter constructed from tarps and tree branches. She was one of the few whose tent had a generator to provide electricity. Delmas 31 camp, Port-au-Prince, March 2010.

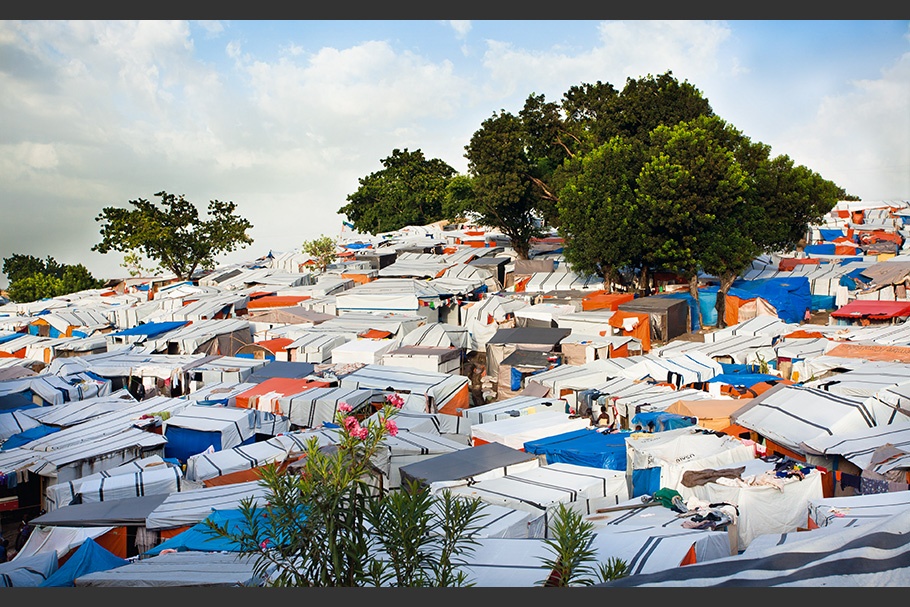

tent-life-temporary-homes-mw19-collection

A tightly packed maze of temporary homes for approximately 55,000 people covers a country club’s nine-hole golf course. Pétionville relief camp, Pétionville, Port-au-Prince, September 2010.

Wyatt Gallery discovered his love for photography as a high school student in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received his BFA in photography from the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University in 1997. One year later, he received a Rosenberg Foundation Grant to complete a photographic project about the spiritual sites of the Caribbean. After spending a month in Trinidad, he decided to relocate there, and with the help of a Fulbright Fellowship, he spent the next two years photographing its diverse cultural history.

Gallery has received numerous accolades including Photo District News’ 30 New and Emerging Photographers to Watch and Photo Annual award and the Center for Documentary Studies’ 25 Under 25: Up-and-Coming American Photographers. He has worked as a professor of photography at the University of Pennsylvania and continues to lecture at schools such as the School of Visual Arts and New York University. His work has been published in several books and magazines such as Esquire, the New York Times, GEO Saison, Mother Jones, and Afar. Gallery’s photographs have been exhibited throughout the world and are in major private and public collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the George Eastman House, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and American Express.

In 2010, Gallery spent the year photographing in Haiti and raising awareness of the tragic living conditions after the earthquake. He published his first monograph Tent Life: Haiti with Umbrage Editions in 2011 and donated the book’s royalties to three NGOs working in Haiti.

Wyatt Gallery

On January 12, 2010, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake hit Haiti while I was on assignment in the Caribbean island of Curaçao. For 13 years, the Caribbean has been my second home and the place where I feel most comfortable. I had photographed the aftermath of natural disasters before: first in January 2005 after a tsunami devastated Southeast Asia and then nine months later after Hurricane Katrina and a failed levee system flooded New Orleans. With Haiti, though, I had a deep connection to the region and its people, making the tragedy all the more personal.

Despite multiple efforts to go immediately to Haiti, I was unable to reach the country in the days following the earthquake. Two months later, five fellow artists and I traveled to Port-au-Prince with Healing Haiti, where we visited the widespread and often chaotic tent cities. Our aim was to assist people in any way we could. While volunteering to deliver clean drinking water, we tapped into our creativity as a resource, by using our art to illuminate the struggles of people living in a disaster stricken city, and by teaching art to youth. Although we found sadness and suffering among the ruins, we were also touched by the uplifting spirit of the Haitian people and their sense of hope, resilience, and at times, joy.

I returned seven months later and continued to photograph the living conditions in the massive tent cities that had become Port-au-Prince’s new settlements. There, I saw something that was not being covered by mainstream media and something that I had noticed previously when photographing the aftermath of the tsunami in Southeast Asia and Hurricane Katrina. That is, although people were frustrated, they kept hope alive and, moreover, maintained their dignity by doing their best to recreate a normal way of life. Residents opened beauty salons, markets, and other small businesses within their tents. They organized and arranged their few remaining belongings, hanging towels and shirts on clotheslines, placing hooks on the walls for purses, and creating makeshift vanities for their toiletries.

These photographs serve to communicate the strength of millions of Haitians who are forced to live amid the formidable health and housing crises that have emerged in the aftermath of the earthquake. This project is also about tent life, and the efforts people go through to maintain their humanity amidst inhuman conditions. As Edwidge Danticat reminds us in the essay she contributed to my book Tent Life: Haiti, “Tent life is not to be idealized though. It is indeed about misery and pain. It is about standing up when it’s raining because the floor where you are sleeping becomes a pile of mud….It is about lack of privacy, jobs, food, clean water, sanitation, and waste disposal. It’s about the grave menace of spreading cholera and other infectious diseases. But it is also about what Haiti has always offered: spontaneous and lasting community as well as cooperation. It is about people looking after one another in extremely difficult times, sharing what very little they have. It is about love, dignity, resilience, and, yes, hope.”

—Wyatt Gallery, November 2011

Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (FOKAL) / Soros Economic Development Fund

The Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (FOKAL) seeks to unite civil society across Haiti and nurture local and international alliances to restore peace, foster economic development, and promote urban revitalization. On January 15, 2010, three days after a massive earthquake in Haiti, the Open Society Foundations, guided by FOKAL, gave an initial grant of $4 million to support relief efforts. Through its local foundations and various programs, the Open Society Foundations have given some $50 million to support public libraries, community water programs, and urban revitalization in Port-au-Prince. The Soros Economic Development Fund, a sister foundation of the Open Society Foundations that works to alleviate poverty, has helped thousands of Haitian entrepreneurs secure microcredit loans.