20030130-moller-mw07-collection-001

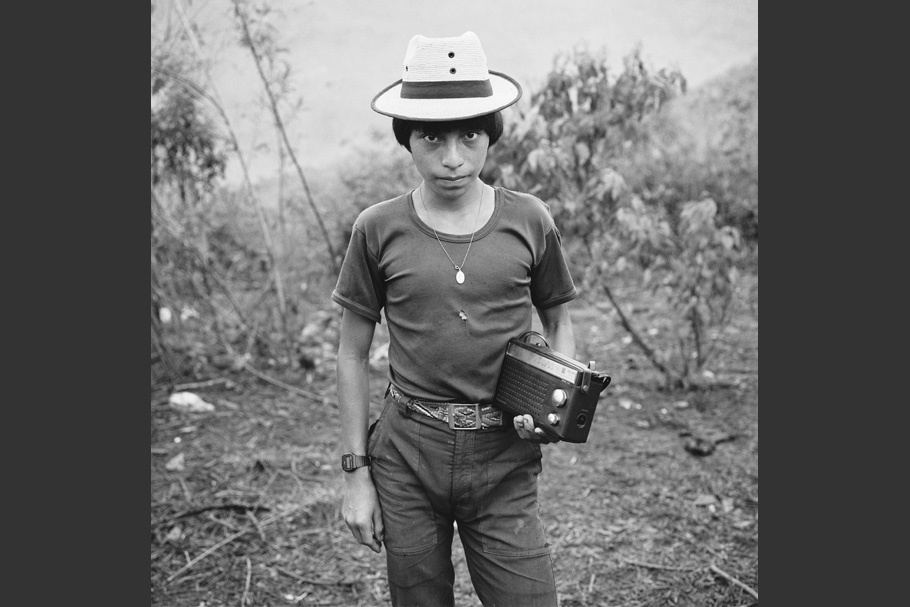

Domingo poses with his radio, one of his family’s few nonessential possessions and virtually their only link to the outside world. One night in 1980, when Domingo was only three, soldiers took away his older brother and sister. They were never seen again. His mother and father, gathering up Domingo and his two baby brothers, fled that same night. With deep sadness, he said, "Many were killed that night in our village, and the soldiers started burning all the houses. Those that were not killed or burned alive fled into the mountains."

Cabá region, the Communities of Population in Resistance of the Sierra, Quiché, Guatemala, 1993.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-002

With her little brother on her back, Ana holds an exploded mortar shell that was fired at the community during an army offensive in 1989.

Cabá region, Communities of Population in Resistance of the Sierra, Quiché, Guatemala, 1993.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-003

A prayer is offered prior to the beginning of an exhumation at the site of a clandestine cemetery in the mountains near the village of Janlay.

Nebaj, Quiché, Guatemala, 2000.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-004

At the height of its "scorched earth" counterinsurgency campaign in the early 1980s, the Guatemalan Army forced villagers to cut down the trees along the roads and major paths so that the guerrillas couldn't hide to ambush soldiers. Although the local Chuj Indians use wood for cooking and to build their small houses, they refused to remove the trunks from where they had fallen, believing that they were sacred.

Cordillera de los Cuchumatanes #1, San Mateo Ixtatán, Huehuetenango, Guatemala, 1997.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-005

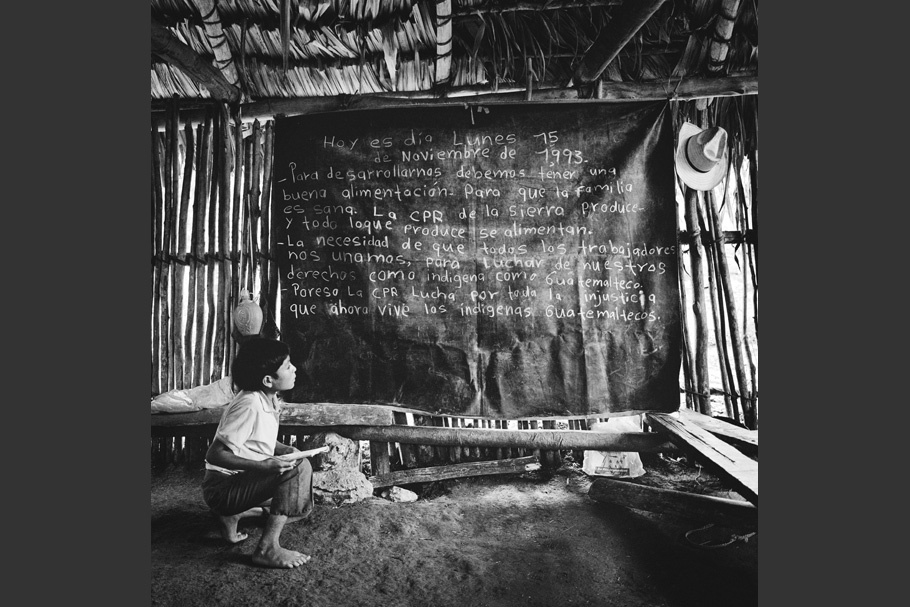

School lesson, Cab region, the Communities of Population in Resistance (CPR) of the Sierra, Quiche, Guatemala. The lesson reads, "Today is Monday the 15th of November of 1993. In order to develop we must have good food, so that the family is healthy. The CPR of the Sierra produces food and all that it produces it feeds itself with. It is a necessity that all of the workers unite ourselves, to struggle for our rights as indigenous people and as Guatemalans. For this reason the CPR struggles against all the injustice now lived by indigenous Guatemalans."

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-006

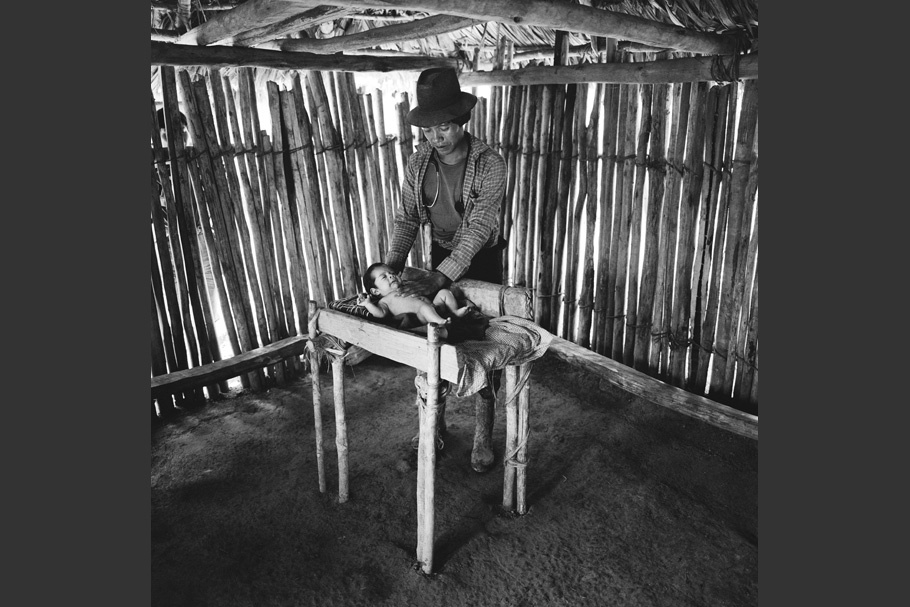

The health clinic.

Xecuxap settlement, Cabá region, Communities of Population in Resistance of the Sierra, Quiché, Guatemala, 1993.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-007

After bathing, Juliana checks her son’s hair for lice.

Primavera del Ixcán, the Communities of Population in Resistance of the Ixcán, Quiché, Guatemala, 2000.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-008

The marriage of Juan and Maria.

Tzucuna settlement, Cabá region, Communities of Population in Resistance of the Sierra, Quiché, Guatemala, 1993.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-009

Two women tend the fire in the community kitchen and cook nixtamal, the corn that will later be ground and made into maza for tortillas. The community kitchen serves visitors from other settlements and encampments.

Cabá region, the Communities of Population in Resistance of the Sierra, Quiché, Guatemala, 1993.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-010

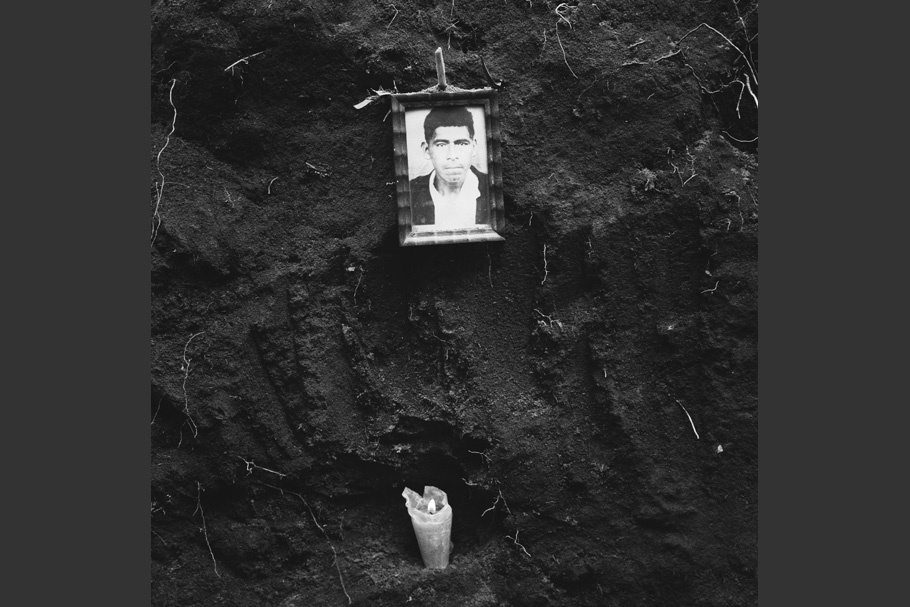

Vicente was 50 years old when he was killed by the army. His wife placed this photograph of him on the wall of the open grave as workers removed his remains.

Janlay, Nebaj, Quiché, Guatemala, 2000.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-011

Sierra Panimaquín #10, Totonicapán, Guatemala, 1997.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-012

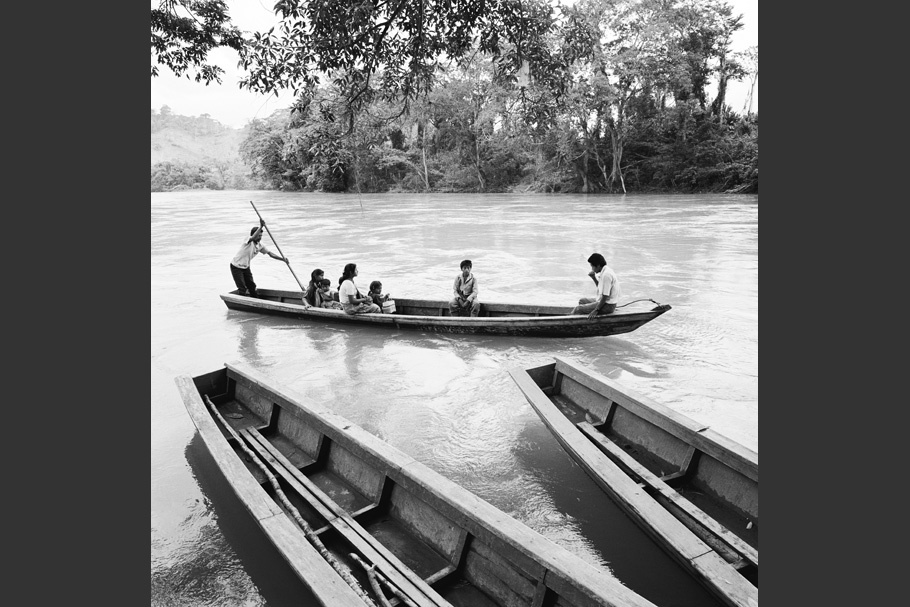

Lanchas in the Río Chixoy, used primarily to ferry people across the river to work the land on the other side, or as transport to other communities. Primavera del Ixcán, the permanent resettlement community occupied by some 300 families of the Communities of Population in Resistance of the Ixcán since they left their jungle hiding places in late 1996.

Ixcán, Quiché, Guatemala, 2000.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-013

Sunday, July 29, 2001. The remains of fifteen people are about to be buried in the cemetery of one of the villages. Pablo, who stands at the center, is burying his father, killed in 1983 by a military patrol. He said:

The truth is that it’s a mixture of sadness and happiness. Sadness to see the remains since they are only bones. But at the same time you try to feel like you have him once again in your arms. It wasn’t possible to reach out your hand and say: ‘Good-bye dad, we’ll see each other again who knows when,’ right? That’s no longer possible. But this moment, today, we are able to recover part of his body, part of him, even if it’s only his remains.

Nebaj, Quiché, Guatemala, 2001.

20030130-moller-mw07-collection-014

Don Santos surveys the area in the woods where he buried his four children – two were killed by the army and two died of hunger and illness while in hiding in these mountains. Thirty people were buried here. As if he had only been waiting to recover the remains of his children, don Santos passed away a month after the exhumation.

Xexocóm, Nebaj, Quiché, Guatemala, 2000.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Jonathan Moller studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and received a BFA from Tufts University. He resides in Denver, Colorado, where he is working on a book that pairs his photographs with testimonies of the repression and violence against indigenous people in Guatemala.

As a photographer and human rights activist, Moller has spent seven of the past eleven years in Central America. One of his photographic projects from that period is El Salvador in the Eye of the Beholder. In Guatemala, he collaborated with human rights organizations supporting uprooted populations and photographed the exhumations of clandestine cemeteries with a forensic anthropology team.

Moller’s photographs have been widely published and are in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the University of California Berkeley Art Museum, among others. Refugees Even After Death: Photographs of Exhumations of Clandestine Cemeteries in Guatemala, funded by the Daniele Agostino Foundation and Amnesty International, is currently touring the United States. A duplicate show is touring Europe.

Moller received the Fellowship Award from the Society for Contemporary Photography in 2002 and the Henry Dunant Prize for Excellence in Journalism in 2001. Moller’s first book, Our Culture is Our Resistance: Repression, Refuge and Healing in Guatemala, was published by powerHouse Books, New York, in September 2004. The Photo District News (pdn) Photo Annual 2005 chose it as one of the 25 best photography books of 2004.

Moller is currently working on a project in Peru with the Peruvian Forensic Anthropology Team (EPAF) photographing family members of the disappeared and exhumations of clandestine cemeteries, as well as a long term project photographing people in transit. His ongoing project in Guatemala with the educational edition of his book Rescatando Nuestra Memoria (together with a separate teachers’ guide and an interactive CD version) continues into its fourth year; the project is formally known as the Educational Program Recovering Our Historical Memory for Civic Education and a Culture of Peace (original name in Spanish: Programa Educativo Rescatando Nuestra Memoria para la Formación Ciudadana y Cultura de Paz); to date 29,000 books, 13,500 teachers guides, and 2,500 interactive CDs have been printed and are being distributed for free and put to use in Guatemalan schools, universities and communities.

Jonathan Moller

Between 1993 and 2001, as a human rights advocate and freelance photographer, I worked with indigenous Mayans uprooted by Guatemala’s long and brutal civil war. Spending much of my time in rural areas, I supported the country’s displaced and refugee populations in their struggle for basic rights. Most recently, I collaborated with the Catholic Church’s Office of Peace and Reconciliation’s forensic anthropology team, documenting the exhumations of clandestine cemeteries.

My work focuses primarily on the communities that emerged from the army’s violent repression of the civilian population in the early 1980s. While tens of thousands of indigenous peasants spilled across the border into Mexico, others fled to remote mountain and jungle areas where they formed highly organized, self-governing Communities of Population Resistance that silently resisted army control and extermination. These communities remained in hiding until the mid-1990s, during which time they were accused by the government of being guerrillas and were hunted by the army. The United States Truth Commission concluded that the United States trained, aided and directly supported the Guatemalan military in their genocidal counterinsurgency campaigns against civilian populations.

After Guatemala’s 36-year civil war ended with the signing of the Peace Accords in late 1996, entire Communities of Population in Resistance migrated from their mountain and jungle refuges to new regions, having negotiated property rights with the government or purchased land with support from Catholic charities. Visiting these newly settled communities in 2000, I began to photograph the people and their tenuous circumstances.

Six years after the signing of the Peace Accords, the country continues to experience a culture of impunity, violence, poverty and exclusion. Guatemala’s civil war led to the death or disappearance of more than 200,000 civilians; hundreds of thousands of others became refugees or displaced people. By the army’s own account, more than 450 villages were wiped off the map during its five-year scorched earth campaign; massacres of women, children and the elderly occurred on a regular basis. As the country moves toward peace, survivors of the war, including the Communities of Population in Resistance, seek the remains of their loved ones who either disappeared or were massacred. Exhumations allow the survivors to begin healing and, as the truth emerges, even seek justice.

My photographs illuminate the strength and dignity of these people, document the atrocities that occurred, and depict the story of the repression and unspeakable violence suffered by the majority of indigenous Guatemalans.

Ten years ago, in those profoundly beautiful mountains and jungles, I married my passions for photography and social justice. I hope that this work speaks to my vision as both an artist and an activist, and especially to the lives of those in Guatemala who survived and resisted death and exploitation and who continue to struggle for their land, their basic rights and their culture.

—Jonathan Moller, January 2003