20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-001

Bullet hole from a stray bullet, with view of downtown Medellin.

Medellin, Colombia, 2002.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-002

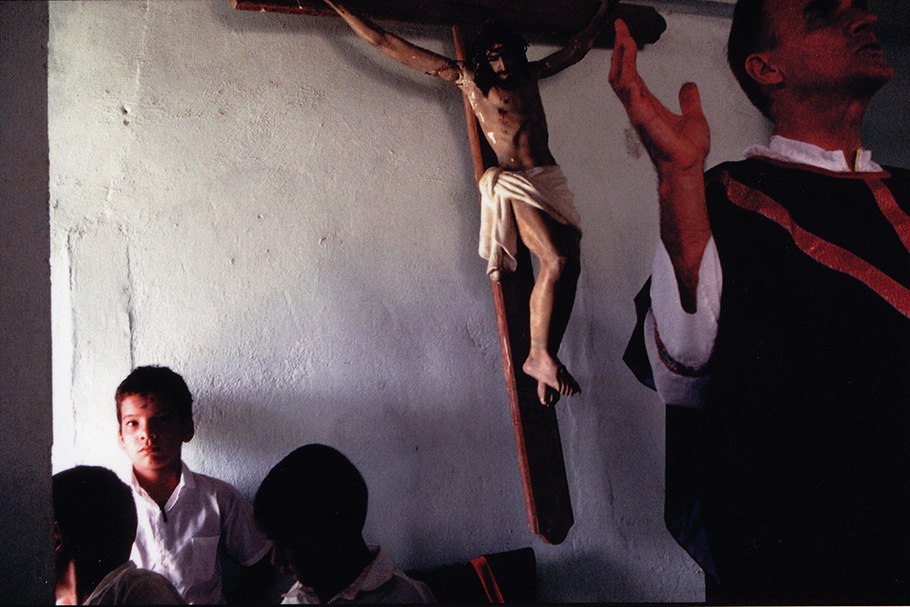

A boy listens as Padre van Hagen, a Catholic priest in the guerrilla-controlled southern state of Caquetá, holds mass in honor of a family assassinated by the United Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Colombia.

Betania, Caquetá, Colombia, 1999.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-003

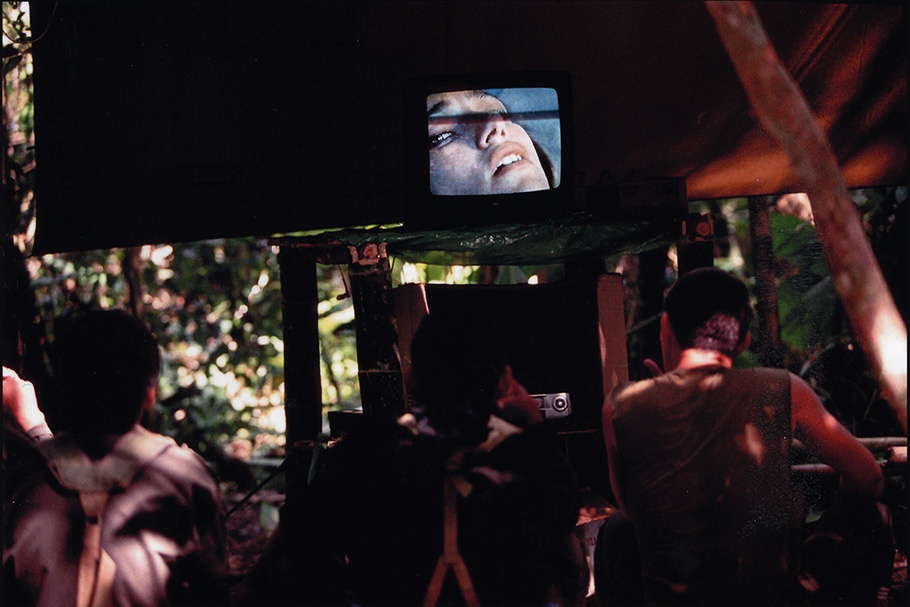

Soldiers of the National Liberation Army relax and watch a video at their base camp.

Arauca, Colombia, 2002.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-004

On a road outside Cúcuta, Norte de Santander, a funeral home worker awaits the arrival of the coroner before removing the body of a victim of the right-wing paramilitary forces (United Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, or AUC from its Spanish initials). In this region, like many others under its control, the AUC frequently assassinates alleged guerrilla collaborators or suspected petty criminals, often in cooperation with local government forces.

Cúcuta, Norte de Santander, Colombia, 2003.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-005

Guerrillas of the Domingo Laìn Front of the National Liberation Army exercise at a clandestine jungle camp in the state of Arauca. This guerrilla front is responsible for a large number of attacks on the Caño Limòn pipeline.

Arauca, Colombia, 2002.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-006

Soldiers of the Colombian Army provide security while a helicopter brings in supplies to repair the Caño Limón oil pipeline, which was sabotaged by guerrilla forces in August 2001.

Arauca, Colombia, 2001.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-007

Soldiers of the U.S.-trained 18th Counter-Insurgency Brigade pray as they take off in Black Hawk helicopter—supplied by the United States—toward territory held by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas in the state of Meta. These troops were deployed to pressure the FARC to release four U.S. ornithologists who had been kidnapped while bird-watching.

Meta, Colombia, 1998.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-008

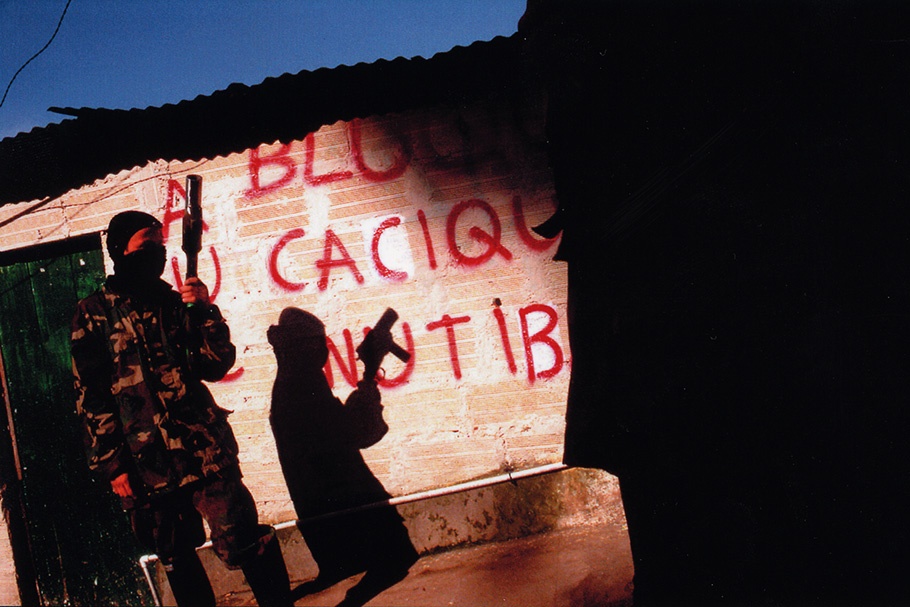

The United Peasant Self-Defense Forces systematically kill suspected guerrilla collaborators, trade unionists, and petty criminals, often with the tacit support of government forces.

Cúcuta, Norte de Santander, Colombia, 2003.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-009

“Gueso” (foreground), a 16-year-old, battle-hardened member of the United Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), holds a homemade grenade launcher while on sentry duty in the San Pablo neighborhood of Medellín, which is under AUC control. “Gueso,” a professional assassin from the age of 12, was recruited by the AUC for his skills in execution, torture and urban warfare.

Medellín, Colombia, 2002.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-010

Crowds purchase flowers at a Bogotá florist on Mother’s Day, 2003. Every year, there are more homicides reported on Mother’s Day than on any other date.

Bogotá, Colombia, 2003.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-011

A resisting cow is dragged to the slaughterhouse.

Puerto Rico, Caquetá, Colombia 2000.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-012

Alongside the Guayas River, in Caquetá, farmers wait for the ferry to bring supplies. The government ceded this area, popularly referred to as Farclandia, to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas as an incentive to peace talks.

San Vicente de Caguán, Caquetá, Colombia, 2000.

20040610-ferry-mw09-collection-013

Men on security detail observe a demonstration of peasants protesting abuses by the United Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, which they claim is allied with oil companies in the region.

Tame, Arauca, Colombia, 2002.

Stephen Ferry is a freelance documentary photographer based in New York City and Bogota, Colombia. Over 15 years of international travel, Ferry has concentrated on long-term reportage on issues of historic change and human rights. He has covered the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, the rise of militant Islam in North Africa, forensic anthropology and the legacy of dictatorship in Argentina, El Salvador, and Ethiopia, electoral fraud in the 2000 US presidential election, and the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center.

Ferry’s 1999 book, I Am Rich Potosí: The Mountain that Eats Men (Monacelli Press), documented the lives of silver miners in Potosí, Bolivia, over an eight-year period. Since 2000, Ferry has focused his work on Colombia, carrying out assignments for GEO, National Geographic, Time, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, and The New York Times. He is represented by Redux Pictures in New York.

Stephen Ferry

Not long ago, after hearing that I was leaving on assignment to a guerrilla-held area of Colombia, a colleague remarked, “Oh, you’re going to cover the drug war.” The assumption that drugs fuel Colombia’s civil war underlies U.S. policy toward the country and shapes the way it is covered in the press. Many editors view the “drug war” as old news, a story that goes back to the 1980s and has no end in sight. Colombia no longer provides the sense of urgency that drives a major news story. Few people outside the region know that, over the last three years, Colombia has suffered over 500 massacres, the killing of thousands, and an estimated 2 million internal refugees. The causes of the conflict reach back hundreds of years, long before the world market for narcotics existed.

The current civil war—between left-wing guerrillas and state and allied paramilitary armies—is the offspring of La Violencia, a ghastly period of fighting in the mid-20th century between followers of the Liberal and Conservative parties that took the lives of over 200,000 people. The Violence was a sequel to the War of a Thousand Days, at the end of the 19th century, which, in turn, drew its fury from the 12 civil wars fought over the course of the 1800s.

Colombians have no single answer that explains their collective nightmare. Many believe Colombia’s history of pillage and murder began with the Spanish conquistadors, and religious intolerance and cruelty toward the “Other” were no doubt a part of the colonists’ mentality. However, this legacy is shared by all of Latin America, from Patagonia to Cuba, yet no other country has suffered centuries of fratricide like Colombia. The armed left blames Colombia’s extreme social injustice; but, again, Colombia has no monopoly on economic exploitation or social inequity.

Colombia’s war remains a mystery. It calls for a visual approach that does not provide ready answers, but instead tries to convey the hidden meanings inscribed in the color, chaos, and surrealism of Colombian life. A point of reference for my work is the opening sentence of The Vortex, Jose Eustasio Rivera’s 1924 epic novel of a Colombian youth’s coming of age: “Before I ever knew passion for a woman, I bet my heart on chance, and I lost it to The Violence.” My images attempt to capture the psychological, sexual, and mythical aspects of Colombia’s war.

I hope to present a nuanced view of Colombia that is essential to any evaluation of U.S. policy toward Colombia. Since 2000, the United States has committed over $3 billion in military aid to support Colombian security forces in their fight against leftist guerrilla armies. These guerrilla armies, to varying degrees, finance their cause through trafficking cocaine and heroin. But the brutal paramilitary armies that work closely with Colombian security forces are also major international drug dealers. The complexity of Colombia’s conflict means that U.S. military aid inevitably has unintended effects, leading to more violence and further erosion of the rule of law.

—Stephen Ferry, June 2004