20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-001

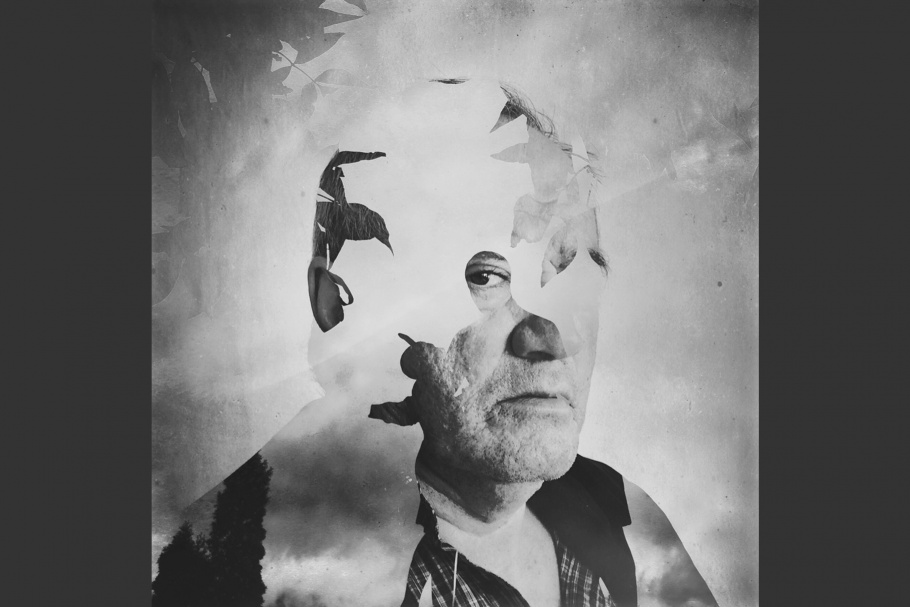

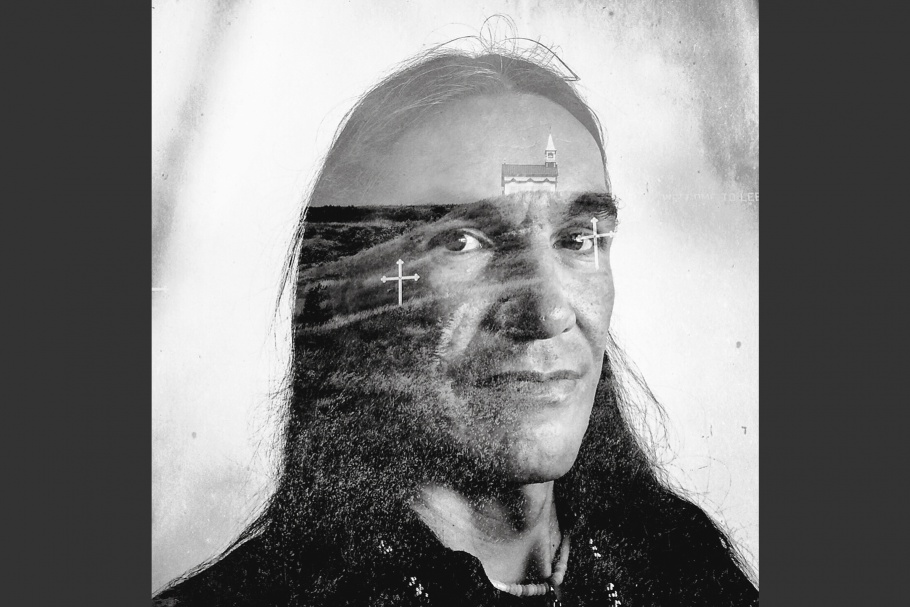

Deedee Lerat

Marieval Indian Residential School

1967–1970

“When I was eight, Mormons swept across Saskatchewan. So I was taken out of residential school and sent to a Mormon foster home for five years. I’ve been told I’m going to hell so many times and in so many ways. Now I’m just scared of God.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-002

![Stuart Bitternose. Gordon Indian Residential School. 1946–1954. “After I’d had enough of that place, one day I jumped the eight-foot high fence and I took off down the highway. I found a farm, and I asked if I could work, and I stayed there for two and a half years on a salary of a dollar a day. I told the farmer I’d run away [from residential school], and he said he didn’t care—and if anyone came looking for me he’d chase them off for trespassing. He saved me.” Photo credit: © Daniella Zalcman A street superimposed on a man wearing a cowboy hat.](../../sites/default/files/styles/mw_collection_910/public/photos/20170925-zalcman-mw24-002-1820.jpg%3Fitok=2moH0oCo)

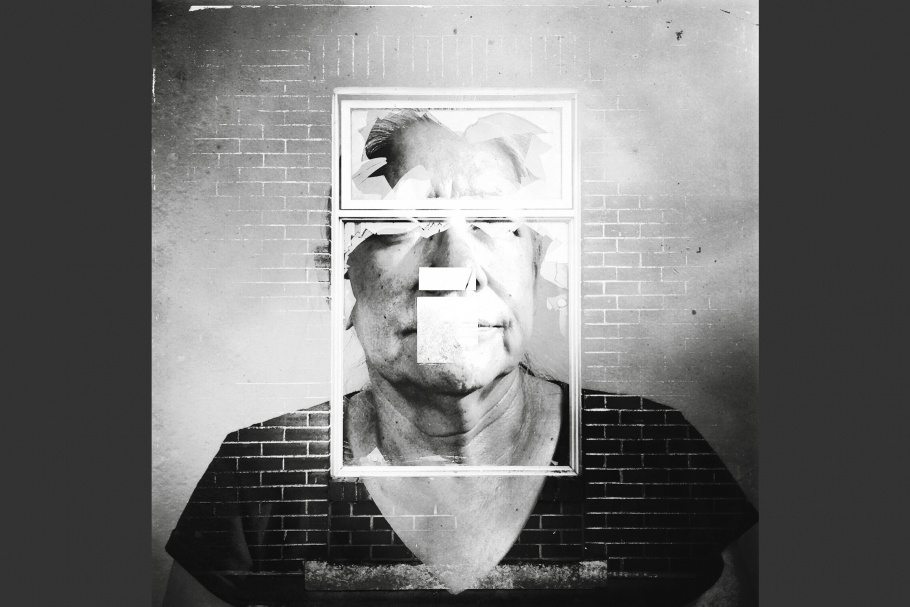

Stuart Bitternose

Gordon Indian Residential School

1946–1954

“After I’d had enough of that place, one day I jumped the eight-foot high fence and I took off down the highway. I found a farm, and I asked if I could work, and I stayed there for two and a half years on a salary of a dollar a day. I told the farmer I’d run away [from residential school], and he said he didn’t care—and if anyone came looking for me he’d chase them off for trespassing. He saved me.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-003

![Seraphine Kay. Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School. 1974–1975. “I was raped at school. He was an old man, the janitor. I didn’t tell anyone for decades, because I thought people would judge me. The only person I ever told was my mother [who went to Muskowekwan Indian Residential School]. All she said was, ‘That’s how I was brought up, too.’” Photo credit: © Daniella Zalcman A woman with a picture of leaves superimposed over her face.](../../sites/default/files/styles/mw_collection_910/public/photos/20170925-zalcman-mw24-003-1820.jpg%3Fitok=aTfrc0ym)

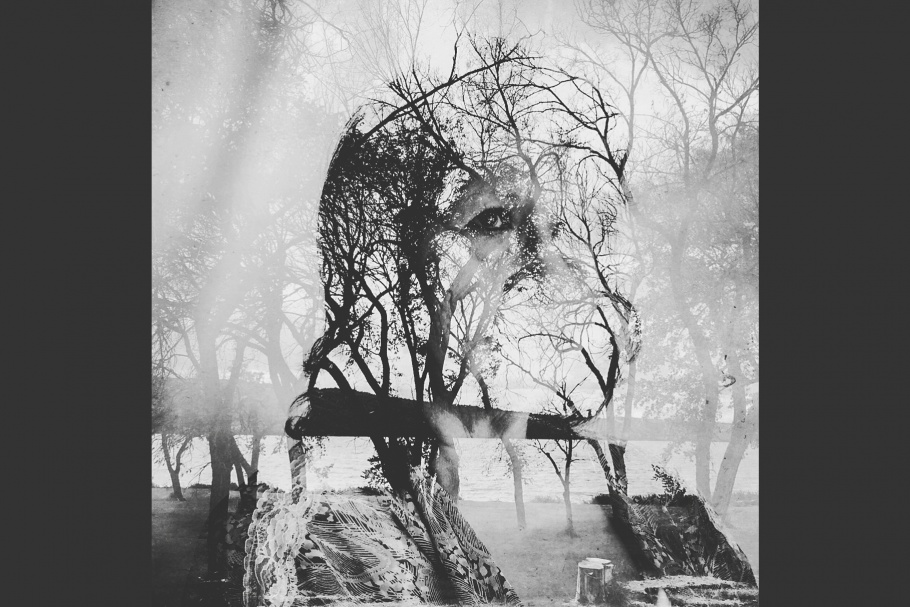

Seraphine Kay

Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School

1974–1975

“I was raped at school. He was an old man, the janitor. I didn’t tell anyone for decades, because I thought people would judge me. The only person I ever told was my mother [who went to Muskowekwan Indian Residential School]. All she said was, ‘That’s how I was brought up, too.’”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-004

![Rick Pelletier. Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School. 1965–1966. “My parents came to visit and I told them I was being beaten. My teachers said that I had an active imagination, so they didn’t believe me at first. But after summer break they tried to take me back, and I cried and cried and cried. I ran away the first night, and when my grandparents went to take me back, I told them I’d keep running away, that I’d walk back to Regina [capital of Saskatchewan] if I had to. They believed me then." Photo credit: © Daniella Zalcman A man's face with a cross and text superimposed on him.](../../sites/default/files/styles/mw_collection_910/public/photos/20170925-zalcman-mw24-004-1820.jpg%3Fitok=a9O_5zay)

Rick Pelletier

Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School

1965–1966

“My parents came to visit and I told them I was being beaten. My teachers said that I had an active imagination, so they didn’t believe me at first. But after summer break they tried to take me back, and I cried and cried and cried. I ran away the first night, and when my grandparents went to take me back, I told them I’d keep running away, that I’d walk back to Regina [capital of Saskatchewan] if I had to. They believed me then.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-005

Grant Severight

St. Philips Indian Residential School

1955–1964

“We, as a people, have normalized every conceivable dysfunction that we experienced in residential school. Negativity is transmitted—and if we don’t deal with it, we pass it on. Even in school, kids who themselves were terrorized grew up to be abusers. We need to figure out how to heal from that.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-006

Elwood Friday

St. Philips Indian Residential School

1951–1953

“I’ve never told anyone what went on there. It’s shameful. I am ashamed. I’ll never tell anyone, and I’ve done everything to try to forget.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-007

Rosalie Sewap

Guy Hill Indian Residential School

1959–1969

“We had to pray every day and ask for forgiveness. But forgiveness for what? When I was seven, I started being abused by a priest and a nun. They’d come around after dark with a flashlight and would take away one of the little girls almost every night. ... You never really heal from that. I turned into an alcoholic and it’s taken me a long time to escape that. I can’t forgive them. Never.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-008

Valerie Ewenin

Muskowekwan Indian Residential School

1965–1971

“I was brought up believing in the nature ways, burning sweet grass, speaking Cree. And then I went to residential school and all of that was taken away from me. And then later on, I forgot it, and that was even worse.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-009

Selina Brittain

Marieval Indian Residential School

1954–1962

“I believe that they thought they were teaching us. I believe that they thought that assimilating us into their way of life would help us. But they changed us into something we weren’t—and there was nothing wrong with our way of life before. That’s what they still don’t understand.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-010

Mike Pinay

Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School

1953–1963

“It was the worst 10 years of my life. I was away from my family from the age of six to 16. How do you learn about family? I didn’t know what love was. We weren’t even known by names back then. I was a number … 73.”

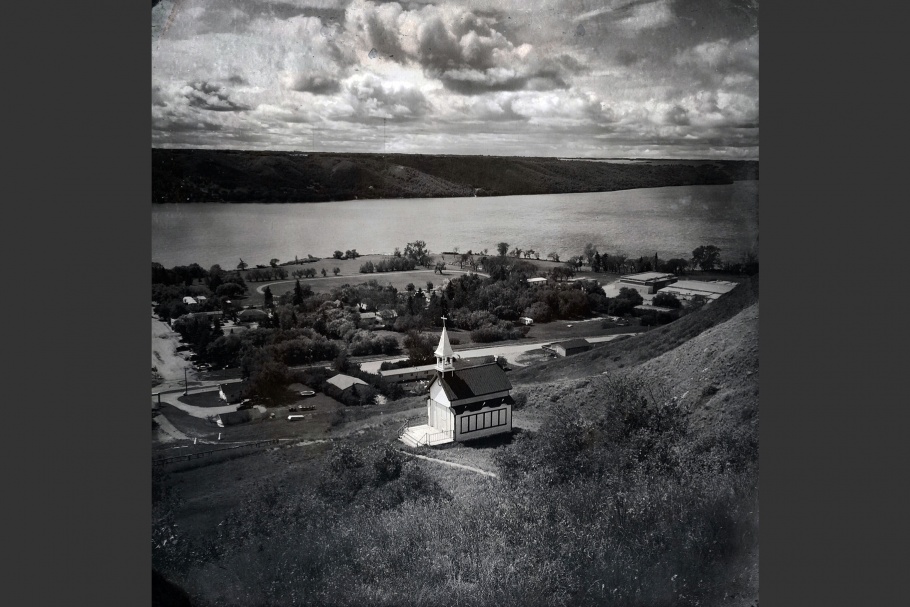

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-011

Lebret, Saskatchewan was home to the Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School, which operated under the federal government and Catholic Church from 1884 to 1969, and under the governance of the Star Blanket Cree Nation from 1973 to 1998. Of all the original school structures, only one building remains (visible on the far right side of this photo).

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-012

Gary Edwards

Ile-a-la-Crosse Indian Residential School, 1970–1973

St. Michael’s Indian Residential School, 1974–1976

Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School, 1976–1978

“I remember after mass every Monday, the head priest would set a large mason jar on the podium. He and two helpers would lock the church doors, and then put on those 1930s canister gas masks. Then they’d open the mason jars and just watch us. We never knew what was happening, but within a few minutes kids would start vomiting or twitching or foaming at the mouth. Looking back, I don’t know, but I think it was mustard gas.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-013

The only road from Beauval Indian Residential School led straight to the Beaver River. Students routinely tried to run away, but either were too small to swim across or drowned trying. An estimated 6,000 children died while at boarding school, from malnourishment, physical abuse, failed escape attempts, disease, or fire. Death toll estimates are almost certainly on the low side, as the Canadian government stopped recording student deaths in the 1920s “after the chief medical officer at Indian Affairs suggested children were dying at an alarming rate.” In instances of mass death, such as when Beauval suffered a fire in 1927 and an outbreak of measles in 1936, children were often buried in unmarked mass graves, making definitive figures even more difficult.

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-014

![Marcel Ellery. Marieval Indian Residential School. 1987–1990. “I ran away 27 times. But the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police] always found us eventually. When I got out, I turned to booze because of the abuse. I drank to suppress what had happened to me, to deal with my anger, to deal with my pain, to forget. Ending up in jail was easy because I’d already been there.” Photo credit: © Daniella Zalcman A fence superimposed on a person's face.](../../sites/default/files/styles/mw_collection_910/public/photos/20170925-zalcman-mw24-014-1820.jpg%3Fitok=-mS6x1PD)

Marcel Ellery

Marieval Indian Residential School

1987–1990

“I ran away 27 times. But the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police] always found us eventually. When I got out, I turned to booze because of the abuse. I drank to suppress what had happened to me, to deal with my anger, to deal with my pain, to forget. Ending up in jail was easy because I’d already been there.”

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-015

Interior of the Muskowekwan Indian Residential School, which operated from 1889 to 1981. Muskowekan is one of the last schools still standing in Saskatchewan.

20170925-zalcman-mw24-collection-016

Glen Ewenin

Gordon Indian Residential School, 1970–1973

Muskowekwan Indian Residential School, 1973–1975

“Residential school affects how you see the world. I can’t fit into the public anymore, I don’t feel like a normal person. I don’t even notice myself teaching my kids to be afraid of authority. But it’s made me such a negative person. It changes everything.”

Daniella Zalcman (American, b. 1986) is a documentary photographer based in London and New York. She is a multiple grantee of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, an International Women’s Media Foundation fellow, and member of Boreal Collective. Her work often focuses on the legacies of Western colonization.

Zalcman's ongoing project, Signs of Your Identity, has received the FotoEvidence Book Award (2016), the Magenta Foundation Bright Spark award (2016), the Magnum Foundation Inge Morath Award (2016), the Arnold Newman Prize (2017), and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award (2017). She graduated from Columbia University with a degree in architecture in 2009. The Open Society Moving Walls Grant will support the expansion of the Signs of Your Identity project to include the United States, where 59 Indian residential schools still operate today.

Daniella Zalcman

Beginning in the 1870s, the Canadian government operated a network of Indian residential schools that separated Indigenous children from their parents to weaken cultural and family ties and forcibly assimilate them into Euro-Christian Canadian culture. Indian agents hired by the government would take children as young as two or three years old from their homes and send them to church-run boarding schools. Teachers at these “residential” schools punished the children for speaking their Native languages or observing any Indigenous traditions. School staff also routinely sexually and physically assaulted the children and, in some extreme instances, subjected them to medical experimentation and forced sterilization.

The last residential school closed in 1996. The Canadian government issued its first formal apology in 2008. Former residential school students—with the Assembly of First Nations and Inuit organizations—have sued the government and churches, resulting in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. The agreement called for compensation and the establishment of The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

The lasting impact of these residential schools is immeasurable. So many children died while in the system that it was common for residential schools to have their own cemeteries. Languages disappeared and sacred ceremonies were criminalized and suppressed. The Canadian government has officially termed the residential school system a cultural genocide.

Signs of Your Identity combines portraits of survivors layered with images that reference their memories attending residential schools. The work honors the 80,000 living survivors and their path to personal and formal reconciliation.

—Daniella Zalcman, October 2017